The Use Case for Relative Position Embeddings

We’re in 2022 but many of our most popular causal language models (LMs), including GPT-3, still use absolute positional embeddings. I believe we should stop using those and move to relative positional embeddings such as ALiBi. Deepmind’s Gopher and BigScience’s BLOOM already use relative positioning methods, and I’ve heard that multiple upcoming models also will, and so hopefully this post will help in encouraging the remanining holdouts to follow suit.

Imagine you’re building the next version of a causal code prediction model like Codex. When we train an LM like this, due to GPU memory limitations, we must pick a finite sequence length, say 4,000 tokens, to train the model on. If at inference time, users only want to make predictions in code files shorter than 4,000 tokens, we’re good. But if a user wants to make a prediction for token 4,001, it would be impossible with absolute position embeddings. If you use learned position embeddings, feeding 4,001 tokens to your LM will simply throw a runtime exception (there is no 4,001 position representation). If you use sinusoidal position embeddings, the model will run given 4,001 inputs, but as we show in the ALiBi paper, it will produce really bad predictions (for any token beyond the first 4,000).

Relative positional methods like ALiBi solve this. The T5 bias is another good option, although personally I prefer ALiBi because our paper shows it obtains better results and also it’s faster and doesn’t require any trainable parameters.

The rotary method has shown some strong results when evaluating sequences that are shorter than or equal to train length, but in our paper we show that it is not able to extrapolate to longer sequences. In addition, it is slower than ALiBi and the absolute positional methods. Lastly, while some people consider it a relative position embedding method, in my opinion, that’s incorrect. Rotary simply element-wise multiplies position representations by the word representations (instead of adding position reps to word reps, as is done in the absolute methods). This means that Rotary still employs position embeddings, which in my view makes it an absolute position method, not a relative one. This thread has more details on why I believe absolute position methods are not the way to go.

Can’t I just use an absolute position method and a sliding window to extrapolate? Short answer: Depending on how you implement this, it either won’t work or will be very very inefficient.

Details: Absolute position embeddings are battle tested and so when engineers want to build LMs that can handle longer sequences, one of the first ideas they have is to use a sliding window with an absolute position embedding method. So if we go back to our Codex example from before, we would train the same 4,000 token LM, but at inference, we would limit the attention sublayer to only attend to the last 4,000 tokens. So when we input 4,001 tokens we would only attend to tokens 2 to 4,001 and when we input 4,002 tokens we would only attend to tokens 3 to 4,002 and so on.

There are two ways to do this:

- The simpler approach is just to re-encode everything at every timestep. So in the first feedforward pass of the LM we encode the first 4,000 words, and then in the second feedword pass when we’re looking at words 2 to 4,0001, we discard everything from before and re-encode everything even though there’s an overlap of 3,999 of the words between the two runs. This will work, but is very inefficient. You have to re-encode everything during each forward pass beyond the first 4,000.

- In the second approach, we don’t re-encode previously encoded tokens. This will just lead to really bad predictions (I’ve tested this). This is because the same token will be assigned to different positions during subsequent inference runs, which means that its cached representation is invalid. See visualization below.

In both of these approaches, when we’re not extrapolating (i.e. when we’re doing inference on tokens 1 to 4,000), we do normal LM inference. So for example, when token 600 comes in, we have already computed representations for tokens 1 to 599, so we attend to those representations and only have to construct new outputs for token 600. As mentioned above, if we don’t use a relative position method like ALiBi, continuing this inference beyond the first 4,000 tokens will either just produce really bad predictions or it could work but very slowly, if we re-encode the past tokens. Using ALiBi means we get to continue doing inference much beyond token 4,000 without needing to re-encode anything.

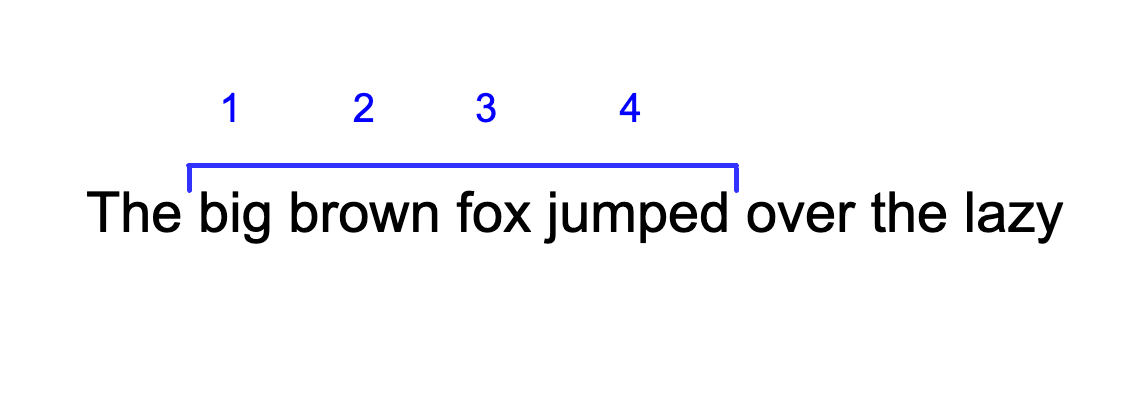

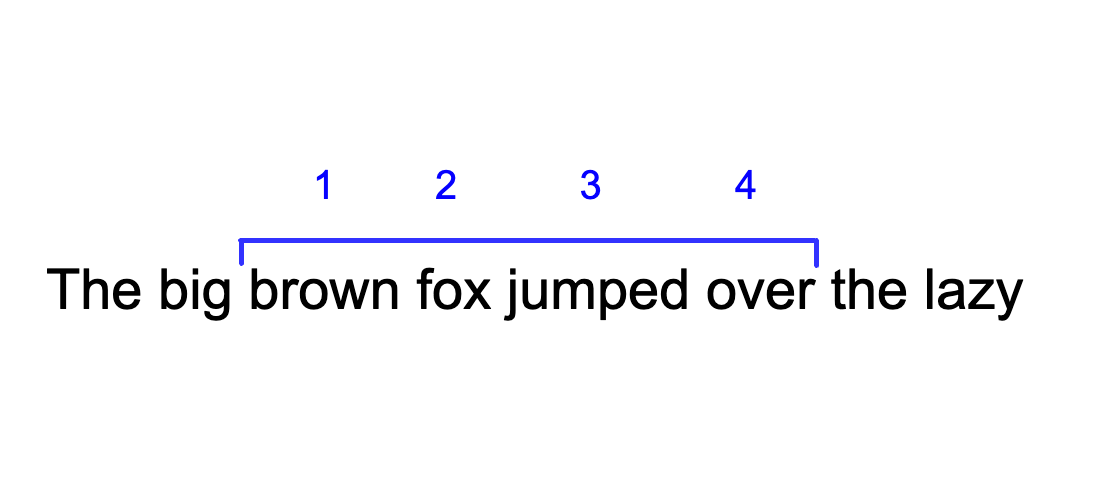

To visualize approach 2 from above, I have a toy input sentence here with a toy language model, whose context size is 4 tokens. We see two subsequent inference passes.

Let’s look at the token ‘jumped’ in these two subsequent forward passes with the sliding window + absolute embeddings approach. ‘Jumped’ was assigned position 4 in the initial forward pass, and then if we use this sliding window approach we would have to treat ‘jumped’ as position 3 in the next forward pass, even though we need to attend to the old cached representation in which it had position 4. This weirdness that the model definitely didn’t experience during training just leads it to produce very bad predictions. This approach does not work.

Edit: Shortly after I wrote this blog post I was made aware of this new paper which reveals new evidence showing the weakness of absolute position embeddings.

To learn more about ALiBi and relative position embeddings in general, watch my lecture here: